After some experiences with Japanese Soto Zen and Tibetan Buddhism, in 1972 Jacob Perl meets Zen Master Seung Sahn in Providence. The latter just migrated to the US, and is working in a laundromat for his living. This encounter is the initial seed for the establishment of the Kwan Um School of Zen, which will grow constantly in the following years as an international institution rooted into the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism.

A Dharma-transmission from teacher to student is based on a long term and intense relationship, with many years of common practice and common living. Jacob Perl became a Ji Do Poep Sa Nim (JDPSN, Dharma teacher) in 1984, and a Zen Master in 1993. From that point in time he is the 79th patriarch in the lineage of Zen Master Seung Sahn, a lineage started with the historical Buddha, developed through India and China, eventually being introduced in Korea in the first centuries a.C. where it continues to exist until our days. Flowering schools and great teachers , a story through the centuries and through various realities. When young Seung Sahn experienced enlightenment in the Korean mountains, he searched for somebody who could confirm his attainment. Here we arrive to Ko Bong Soen Sa Nim, who made Seung Sahn as his only successor. Who stands behind him? Let’s make further steps back: before Kobong we find Mangong (1871-1946), and before Mangong there is Kyongho (1849-1912). So before reaching Seung Sahn and finally Jacob Perl, let’s have a look at the earlier generations and their style of Zen in the 19th Century. A glimpse of the development of forms and teachings – a legacy still vivid today, also representative of other schools in nearby cultures.

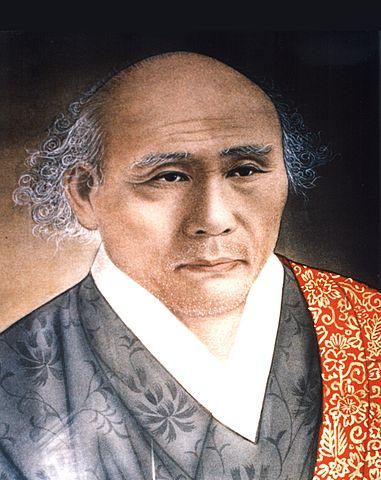

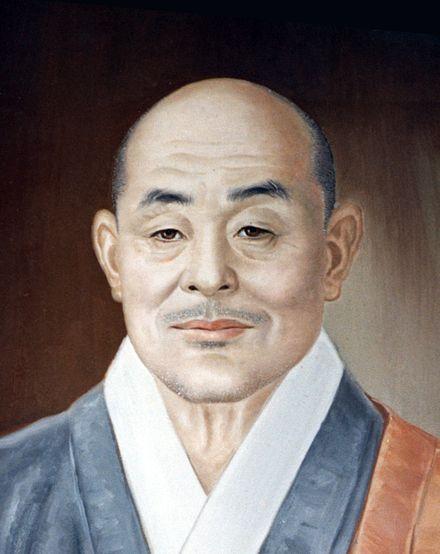

1. Kyong Ho (the 75th Patriarch)

From Wikipedia: Kyong Ho Seonsa (Korean: 경허선사, Hanja: 鏡虛禪師, 1849—1912) was a famous Korea Sŏn master, and the 75th Patriarch of Korean Sŏn. His original name was Song Tonguk; and his dharma name was Sŏng’u. He is known as the reviver of modern Korean Sŏn Buddhism. Song Tonguk was born in southern Korea (Chŏnju, Chŏlla province), and entered the sangha at the age of nine in 1857. He ordained at Ch’ŏnggye monastery located at Kwach’ŏn, in the Kyŏnggi province. The young monk studied under the tutelage of Kyehŏ–sŏnsa. When he was 14, in 1862, Kyehŏ–sŏnsa disrobed and sent Kyŏnghŏ–sŏnsa to Manhwa–sŏnsa for further study at Tonghak–sa. Kyŏnghŏ soon distinguished himself as a sūtra-lecturer grew until a dramatic incident took place in 1879 while Kyŏnghŏ was travelling to Seoul to meet his previous teacher Kyehŏ–sŏnsa. On the way he entered a village looking for shelter from a rainstorm and discovered that the entire inhabitants of the village had died from an epidemic. Kyŏnghŏ came to understand that his knowledge of Buddhist sūtras did not help him in the issues of life and death. When Kyŏnghŏ returned to his monastery, he summarily dismissed all of his students, and began serious Sŏn meditation practice. The kongan he worked with was Master Lingyun’s (771-853) “The donkey is not yet done and the horse has already arrived.” He understood his kongan when he was reading, “Even though I should become a cow, there will be no nostrils.” Kyŏnghŏ attained enlightenment on November 15, 1887.

Kyŏnghŏ now devoted himself to teaching Sŏn at various monasteries including Pŏmŏ–sa, Haein–sa and Sŏnggwang–sa until his disappearance in 1905. His activities from 1905 until his death in 1912 are not clear. Some claim that he wandered around in the northern part of Korea as a beggar; and other sources report that he lived a life of a layperson, letting his hair grow and teaching Confucian classics.

The importance of Kyŏnghŏ in Korean Buddhism is because his main disciples, Suwŏl–sŏnsa (1855–1928), Hyewŏl–sŏnsa (1861–1937), Man’gong–sŏnsa (1871–1946), and Hanam–sŏnsa (1876–1951) played an extremely important role in the transmission of the dharma. Kyŏnghŏ is recognized as the founder of modern Korean Sŏn Buddhism: he revived Chinul’s idea of kanhwa Sŏn and also lived the life of a bodhisattva with his unobstructed activities in the manner of his distant predecessor Wŏnhyo (617-686). Kyŏnghŏ was also a great proponent of teaching lay Buddhists Sŏn meditation which was revolutionary because he devoted himself to meditation in a hermitage and also lived among the lay Buddhists in the secular world. Kyŏnghŏ’s unconventional life style and eccentric character brought him some criticism as well as fame amongst the followers of the wild freedom style Sŏn masters.

In "Dropping Ashes on the Buddha", edited by Stephen Mitchell, Zen Master Seung Sahn tells the story of Kyong Ho:

At the age of fourteen Kyong Ho began to study the sutras. He was a brilliant student; he heard one and understood ten. By the time he was twenty-three he mastered all the principle sutras. Soon many monks began to gather around him, and he became a famous sutra master. One day Kyong Ho decided to pay a visit to his first teacher. After a few days of walking, he passed through a small village. There were no people in the streets. Immediately he knew something was wrong. As he walked through the main street, he noticed a sign. “Danger: Cholera. If you value your life, go away.” This sign struck Kyong Ho like a hammer, and his mind became very clear. “I am supposed to be a great sutra master; I already understand all of the Buddha’s teachings. Why am I so afraid?” On his way home Kyong Ho thought deeply. Finally he summoned all his students and said, “As many of the sutras as I have mastered, I still haven’t attained true understanding. I can’t teach you any more. I will not teach again until I have attained enlightenment.” All the students went away except one. Kyong Ho shut himself in his room. Once a day the student brought him food, leaving the platter outside the closed door. All day long Kyong Ho sat or did lying-down Zen. He meditated on a kong-an which he had seen in a Zen book: “Before the donkey leaves, the horse has already arrived.” “I am as good as dead,” he thought; “if I can’t get beyond life and death I vow never to leave this room.”

Three months passed.

One day the student went to a nearby town for food. There he happened to meet a Mr. Lee, who was a close friend of Kyong Ho. Mr. Lee said, “What is your Master doing nowadays?” The student said, “He is doing hard training. He only eats, sits and lies down.”

“If he just eats, sits and lies down, he will be reborn as a cow.”

The young monk got very angry. “How can you say that? My teacher is the greatest scholar in Korea! I’m positive that he’ll go to heaven after he dies!”

Mr. Lee said, “That’s no way to answer me.”

“Why not? How should I have answered?”

“I would have said, ‘If my teacher is reborn as a cow, he will be a cow with no nostrils.'”

“A cow with no nostrils? What does that mean?”

“Go ask your teacher.”

When he returned to the temple, the student knocked on Kyong Ho’s door and told him of his conversation with Mr. Lee. As soon as he had finished, to his amazement, Kyong Ho opened the door and, with great luminous eyes, walked out of the room.

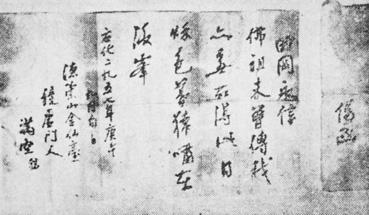

This is the poem which he wrote upon attaining the great enlightenment:

I heard about the cow with no nostrils

and suddenly the whole universe is my home.

Yon Am Mountain lies flat under the road.

A farmer, at the end of his work, is singing.

On the Kwan Um School of Zen page of the Americas there is a list of sayings by Kyong Ho:

Zen Master Kyong Ho (1849-1912) was the Great-grandteacher of Zen Master Seung Sahn

- Don’t wish for perfect health. In perfect health there is greed and wanting. So an ancient said, “Make good medicine from the suffering of sickness.”

- Don’t hope for a life without problems. An easy life results in a judgmental and lazy mind. So an ancient once said, “Accept the anxieties and difficulties of this life.”

- Don’t expect your practice to be always clear of obstacles. Without hindrances the mind that seeks enlightenment may be burnt out. So an ancient once said, “Attain deliverance in disturbances.”

- Don’t expect to practice hard and not experience the weird. Hard practice that evades the unknown makes for a weak commitment. So an ancient once said, “Help hard practice by befriending every demon.”

- Don’t expect to finish doing something easily. If you happen to acquire something easily the will is made weaker. So an ancient once said, “Try again and again to complete what you are doing.”

- Make friends but don’t expect any benefit for yourself. Friendship only for oneself harms trust. So an ancient once said, “Have an enduring friendship with purity in heart.”‘

- Don’t expect others to follow your direction. When it happens that others go along with you, it results in pride. So an ancient once said, “Use your will to bring peace between people.”

- Expect no reward for an act of charity. Expecting something in return leads to a scheming mind. So an ancient once said, “Throw false spirituality away like a pair of old shoes.”

- Don’t seek profit over and above what your work is worth. Acquiring false profit makes a fool (of oneself). So an ancient once said, “Be rich in honesty.”

- Don’t try to make clarity of mind with severe practice. Every mind comes to hate severity, and where is clarity in mortification? So an ancient once said, “Clear a passageway through severe practice.”

- Be equal to every hindrance. Buddha attained Supreme Enlightenment without hindrance. Seekers after truth are schooled in adversity. When they are confronted by a hindrance, they can’t be over-come. Then, cutting free, their treasure is great.

from THOUSAND PEAKS: Korean Zen, Tradition and Teachers by Mu Soeng (Primary Point Press, revised, edition 1991)

The Life and Thought of the Korean Sŏn Master Kyŏnghŏ is a study by Henrik Hjort Sorensen. On sacred-texts.com a talk by Kyong Ho, from the webpage of the Chogyesa Zen Temple of New York the story of the first encounter between Kyong Ho and his future successor Mangong:

A Tale of Zen Masters Man Gong and Kyong Ho

Zen Master Man Gong was Seung Sahn Soen Sa’s Dharma grandfather. As a thirteen year old child, he was studying sutras at the temple Donghaksa in Korea. The day before vacation, everyone gathered to listen to some lectures.

The lecturer said, “All of you must study hard, learn Buddhism, and become as big trees, with which great temples are built, and as large bowls, able to hold many things. The verse says:

“Water becomes square or round according to the shape of the container in which it is placed. Likewise, people become good or bad according to the company they keep. Always keep your minds set on holiness and remain in good company. In this way, you will become great trees and containers of Wisdom. This I most sincerely wish.”

Everyone was greatly inspired by this lecture. At this point, the Sutra Master turned to Zen Master Kyong-Ho, who was visiting the temple, and said, “Please speak, Master Kyong Ho; everyone would like to hear your words of wisdom.”

The Master was quite a sight. He was always unshaven and wore robes that were tattered and worn. Although he at first refused, after being asked again and again, he reluctantly consented to speak.

“All of you are monks. You are to be great teachers, free of ego; you must live only to serve all people. Desiring to become a big tree or a great container of Wisdom prevents you from being a true teacher. Big trees have big uses; small trees have small uses. Good and bad bowls both have their uses. Nothing is to be discarded. Keep both good and bad friends; this is your responsibility. You must not reject any element; this is true Buddhism. My only wish is for you to be free from discriminating thoughts.” Having completed his talk, the Master walked out the door, leaving the audience astonished. The young Man-Gong ran after him, and called out, “Please take me with you; I wish to become your student.”

The Master shouted at him to go away, but the child wouldn’t listen. So he asked, “If I take you with me, what will you do?”

“I will learn. You will teach me.”

“But you are only a child. How can you understand?”

“People are young and old, but does our True Self have youth or old age?”

“You are a very bad boy! You have killed and eaten the Buddha. Come along.”

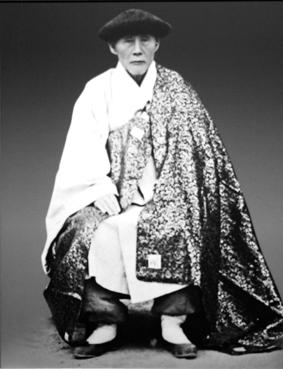

2. Mangong (the 76th Patriarch)

Mangong (만공, 1871 – 1946) or Song Mangong was a Korean Buddhist monk, independence activist, scholar, poet, writer and philosopher, in the period of the Japanese Occupation of Korea.

You can find a more detailed biography on the webspace of Musangsa Temple in South Korea:

Zen Master Man Gong (1871-1946), who was Seung Sahn Sunim’s Grand teacher, was born in a small town in the Korean province of Cholla Buk Do. He became a monk in the year 1883 at the temple Dong Hak Sa on Kye Ryong Mountain. His first teacher was Tae Heo Sunim, but from an early age he began to study with Zen Master Kyong Ho.

Man Gong Sunim attained enlightenment at an early age while staying at Chon Jang Am near Seo San, and after receiving Dharma transmission from Zen Master Kyong Ho, spent most of his life living and teaching near the temple Jeong Hye Sa, on Deok Sung San mountain in Chungchongnamdo.

Man Gong Sunim taught for many years and had numerous Dharma Disciples, including monks, nuns and laymen. During his final days, he resided at Jeon Wol Am, near the top of Deok Sung San mountain. He died at the age of 75, having been a monk for 62 years.

"The Teachings of Man Gong" is a book which was translated and edited in English by Zen Master Dae Kwang, Hye Tong Sunim and Kathy Park in 2009. It contains short teachings listed in chapters. At the end of the book there is also a more accurate biography. We found an online version here. Zen Master Man Gong's name appears also in several Kongans which are part of the practice of the Kwan Um School of Zen. On the webpage of the European Sangha Man Gong's net, the Eleventh Gate:

The Eleventh Gate: Man Gong’s Net

BY ZEN MASTER SEUNG SAHN

One day, Zen Master Man Gong sat on the high rostrum and gave the speech to mark the end of the three month winter retreat. “All winter long you monks practiced very hard. That’s wonderful! As for me, I had nothing to do, so I made a net. This net is made out of a special cord. It is very strong and can catch all Buddhas, Patriarchs and human beings. It catches everything. How do you get out of this net? Some students shouted, “KATZ!” Others hit the floor or raised a fist. One said, “The sky is blue, the grass is green.” Another said, “Already got out; how are you, great Zen Master?” From the back of the room a monk shouted, “Don’t make net!” Many answers were given, but to

each Man Gong only replied, “Aha! I’ve caught a BIG fish!” So, how do you get out of Man Gong’s net?

This is a very famous kong-an. Zen Master Man Gong always taught his students not to make anything. If you practice strongly, don’t make anything and don’t want anything, then you can attain no hindrance. Then this kong-an is not a problem. But if you are thinking, if you still have I, my, me and checking mind, then you cannot get out of the net. This net is life and death and includes everything. Even if you are a Buddha, if you have thinking, you cannot escape the net.

Man Gong’s net is an attack kong-an. “I caught a big fish” is a strong teaching style. It drops down a large (000 size) hook for you. If you touch this fishing hook ,you will have a big problem! It’s just like a boxing match: hit, hit, hit… then you must defend yourself. So, how do you hit Man Gong’s net? How do you take away Man Gong’s idea? Man Gong’s idea made the net. So, you must hit that.

Kong-an practicing is very important—it means, put it all down. In Zen, we say if the Buddha appears, kill the Buddha; if an eminent teacher appears, kill the teacher; if demons appear, kill them. Kill everything that appears in front of you. That means don’t make anything. If you make something, then you have a hindrance. If you can completely put it all down, then you have no hindrance and your direction becomes clear. So, our practicing direction is to make our situation, function, and relationship in this world clear. Why do you eat every day? If that is clear, then our life is clear and we can help this world. Moment to moment our job is to do bodhisattva action and help all beings. Man Gong’s net makes our direction and its function clear. Only help all beings. But that is just an explanation. Explanations can’t help you! An answer is necessary.

This article copyright © 2008 Kwan Um School of Zen.

3. Kobong (the 77th Patriarch)

From Wikipedia: Kobong soen sanim (Korean: 고봉선사, Hanja: 高峯禪師, 1890–1962), the 77th Korean Buddhist Patriarch in his teaching lineage, was a Korean Zen master.

At an early age, Kobong became a monk at Namjangsa. Known for spontaneous and eccentric teaching, he sometimes said that he preferred to teach laypeople because monks were too lazy to practice hard. Kobong never held a position at any temple or established a temple of his own. When he was elderly, his student Seungsahn brought him to Hwagyes in Seoul, South Korea where Kobong died at the temple in 1962. A large granite monument was built in his honor on the hillside overlooking Hwagyesa. Kobong Sunim was Dharma heir to Man-gong Sunim, who was in turn Dharma heir to Kyongho Sunim. Kobong Sunim’s best known student was Seungsahn Sunim (1927–2004), founder of the Kwan Um School of Zen. Seungsahn Sunim received Dharma transmission from Kobong Sunim at 22 years of age. Kobong had never given inka to any monk before he met Seungsahn Sunim and Seungsahn remained his only dharma heir.

From the webpage of the Chogyesa Zen Temple of New York the encounter with Seung Sahn.

Ko Bong Sunim

Zen Master Ko Bong was Zen Master Seung Sahn’s teacher. He became a monk at an early age at Nam Jang Sa, and later attained enlightenment while sitting Kyol Che at Tong Do Sa temple.

Ko Bong Su Nim was renowned for being one of the fiercest keen-eyed masters of his generation, well known for his deep enlightenment and wide actions. He mostly refused to teach Korean monks, calling them arrogant, and preferred only to teach nuns and laypeople. Until he met Seung Sahn Sunim, Zen Master Ko Bong had never given inka or Dharma transmission to any monk.

After getting enlightenment, Seung Sahn Sunim went to check his attainment with Zen Master Ko Bong. Ko Bong Sunim tested him with many difficult Kong-Ans, all of which the young Seung Sahn Sunim passed with ease. Zen Master Ko Bong finally stumped him with the Kong-An “The mouse eats cat food, but the cat bowl is broken.” The two sat facing each other, eyes locked, for close to an hour, when suddenly Seung Sahn Sunim had a breakthrough and gave him the correct answer. Zen Master Ko Bong then said “You are the flower and I am the bee” and soon after gave Dharma transmission to the young Seung Sahn Sunim. Ko Bong Sunim spent his final days at Hwa Gye Sa temple in Seoul, being cared for by his only Dharma heir, and eventually he passed away in 1962.

From Don't-Know Mind: The Spirit of Korean Zen Paperback by Richard Shrobe, which narrates unorthodox teachings by Zen Master Ko Bong.

Zen Master Ko Bong (1890 – 1962) was the greatest of Zen Master Man Gong’sdharma heirs. He was also the most unorthodox and there are many stories of his “bad” behavior. For example, one time Ko Bong stayed at small temple. Every day he worked very hard making a new rice field in the mountains. The temple was very poor, so the food was very bad.

One day when temple’s master had gone to town, Ko Bong suggested to the other monks that they sell the monastery’s cow and go buy wine and meat. Everyone agreed, so they sold the cow and used the money to buy wine and meat. After the evening sitting, they laughed and danced and drank all night in the meditation hall.

When the Zen master returned for the morning sitting, he found all fifty students asleep amidst the debris of the party.

The master wondered where they had gotten the money for this party. He ran to the barn and discovered – no cow! Very angry, he called everyone together in the main hall.

Shouting, the Zen master demanded that his cow be returned. On hearing this, Ko Bong took all his clothes off and crawled around the room on all fours saying, “Moo!”

Delighted, the master hit Ko Bong thirty times on the ass and said, “This is not my cow. This one is too small!” Everyone was relieved. The subject was not brought up again.

After he became a teacher, Ko Bong agreed to give the Five Precepts to the layperson Chung Dong Go Sanim. The ceremony went smoothly until Ko Bong asked the traditional question: “Can these precepts be kept by you or not?”

The layman stood up and said, “If I cannot drink, I die!” Now there was a problem.

But Ko Bong immediately responded, “Then you take only four precepts” Chung Dong Go Sanim became the “Four Precepts Layman,” and got “four precepts enlightenment.”

Ko Bong would frequently test his students with an obscure kong-an:

The mouse eats cat food, but the cat bowl is broken.

What does this mean?

It was through this kong-an that Zen Master Seung Sahn attained his great enlightenment and became Ko Bong’s only dharma heir.

On the webpage of the Musangsa Temple, "Meditation is nothing special", a teaching by Zen Master Ko Bong:

There are three poisons: greed, anger and ignorance. If you put these down then your Buddha nature is like a clear mirror, clear ice, an autumn sky or a very clear lake. The whole universe is in your Danjeon (center). Then your body and mind will calm down and you will be at peace. Your heart will be fresh like an autumn wind – not competitive.

If you attain this level, you’re one half a Zen monk. But, if you are merely satisfied with this you are still ignorant of the way of Buddhas and patriarchs. This is a big mistake because demons will soon drag you to their lair.

Meditation is originally nothing special. Just keep a strong practice mind. If you want to get rid of distractions and get enlightenment, this too is a mistake. Throw away this kind of thinking; only keep a strong mind and practice. Then you will gradually enter “just do it.”

Everyone wants meditation but they think about it in terms of medicine and disease. However, don’t be afraid of what you think of as a disease. Only be afraid of going too slow. Some day you will get enlightenment.

Excerpts from "Wild Dharma Scenes and Broken Precepts" by Zen Master Seung Sahn on Jul 26, 1977, where zen Master Seung Sahn talks about his teacher.

My teacher, Zen Master Ko Bong, taught this way. At Jung Hae Sa Temple in Korea, the schedule consists of three months of sitting followed by three months of vacation. During vacation, everyone collects money or food and brings them back for the sitting period. When Zen Master Man Gong, my grand-teacher, was just beginning the temple, there was no money at all. The students would go around to the homes of lay people, recite the Heart Sutra, get rice or money, and return to the monastery. But when my teacher Ko Bong got rice, he’d sell it at the end of the day and go out drinking. Everyone else came back at the end of a vacation with sacks of rice. All Ko Bong brought back was wine. When he was full of wine he was also full of complaints: “This temple is no good! Man Gong doesn’t understand anything! He’s low-class!”

Once Zen Master Man Gong showed up during one of Ko Bong’s tirades and screamed at him, “What do you understand?” Everybody was waiting to see what would happen. “KO BONG!!!”

“Yes?”

“Why are you always insulting me behind my back?”

Ko Bong looked completely surprised and offended. “Zen Master! I never said anything about you! I was talking about this good-for-nothing Man Gong!”

“Man Gong? What do you mean, Man Gong? I’M Man Gong! What’s the difference between Man Gong and me?”

“KAAAATZ!” Ko Bong yelled, loud enough to split everyone’s eardrums. That ended it.

“Go sleep it off,” Man Gong said, and he left the room.

My teacher was always drunk, used abusive speech, and showed disrespectful behavior. But he always kept a clear mind. “Man Gong? What’s the difference between Man Gong and me?” “KAAAATZ!” That katz is very important — better than money or bags of rice. Ko Bong completely believed in himself.

If you believe completely in yourself, your actions will teach other people. Also you will be able to do any action to help other people. This is the Great Bodhisattva Way.

Ko Bong’s Try Mind by Zen Master Seung Sahn on Mar 1, 1996

Zen Master Ko Bong (1890-1962) was one of the greatest teachers of his time. He was renowned for refusing to teach monks, considering them too lazy and arrogant to be Zen students. He was also very well known for his unconventional behavior.

Ko Bong Sunim didn’t like chanting. He only did sitting meditation, no matter what. That was his practice. One time, as a young monk, he was staying in a small mountain temple. The abbot was away for a few days, so Ko Bong Sunim was the only one around. One morning an old woman climbed the steep road to the temple carrying fruit and a bag of rice on her back. When she reached the main Buddha Hall, she found Ko Bong Sunim seated alone in meditation.

“Oh, Sunim, I am sorry to bother you,” she said. “I have just climbed this mountain to offer these things to the Buddha. My family is having a lot of problems, and I want someone to chant to the Buddha for them. Can you please help me?”

Ko Bong Sunim looked up. Her face was very sad and very sincere. “Of course,” he said. “I’d be happy to chant for you. No problem.” Then he took the bag of rice off her back and they went to the kitchen to prepare the food offering. As they started to wash the fruit he said to her, “I don’t know how to cook rice. You cook the rice, and I’ll go start chanting.”

“Yes, Sunim. Thank you very much.”

Ko Bong Sunim returned to his room to put on his formal robes. But, because he never chanted, he didn’t know any Buddhist chants. So, he dug out an old Taoist sutra from among his things and brought it back to the Buddha Hall. Then he picked up the moktak and started hitting it while reading out of the Taoist book. Usually it’s appropriate to do certain chants for different occasions, like the Thousand Eyes and Hands Sutra, but Ko Bong Sunim didn’t know about this. He only banged the moktak and chanted the Taoist sutra out loud, right from the book. After an hour or so of this, he finished.

The old woman was very, very happy. “Oh, thank you, Sunim. You are very kind. I feel much better now!” She left the temple. As she was walking down the mountain road, she passed the abbot, who was returning to the temple. “Hello, Mrs. Lee, are you coming from the temple?”

“Yes,” she said. “There are many problems in my family right now, so I went up to pray to the Buddha. Ko Bong Sunim helped me.”

“Oh, that’s too bad,” the abbot said.

“Oh, why?”

“Because Ko Bong Sunim doesn’t know how to do any chanting. Maybe someone else could…”

“No, no,” she said. “He did very well. He helped me very much!”

The abbot looked at her. “How do you know how well he did? These are very special chants! Ko Bong Sunim doesn’t know how to do them – he doesn’t know chanting.”

“Yes, I understand.” This woman used to be a nun, so she was quite familiar with all the various chants. She knew that Ko Bong Sunim was only chanting a Taoist sutra. “What is correct chanting? He did it very well. He only chanted one hundred percent. Words are not important. The only important thing is how you keep your mind. He had only try mind – only do it.”

“Oh, yes, of course,” the abbot said. “I suppose mind is very important.” They said good-bye and went their separate ways. When the abbot reached the temple, he found Ko Bong Sunim, seated in meditation. “Did you just chant for Mrs. Lee?”

“Yes.”

“But you don’t know anything about chanting.”

“That’s right,” Ko Bong Sunim said. “I don’t know anything about chanting. So I just chanted.”

“Then what kind of chants did you do?” the abbot asked.

“I used an old Taoist book.”

The abbot walked away, scratching his head.

This is a very interesting try-mind story. It means, from moment to moment only “do it.” Only keep a try mind, only one mind: do it mind. When chanting, sitting or bowing, only do it. Practicing will not help if you are attached to your thinking, if your mind is moving. Taoist chanting, Confucian chanting, Christian chanting, Buddhist chanting: it doesn’t matter. Even chanting, “Coca Cola, Coca Cola, Coca Cola…” can be just as good if you keep a clear mind. But, if you don’t keep a clear mind, even Buddha cannot help you. The most important thing is, only do it. When you only do something one hundred percent, then there is no subject, no object. There’s no inside or outside. Inside and outside are already one. That means you and the whole universe are one and never separate.

The Bible says, “Be still, and know that I am God.” When you are still, then you don’t make anything, and you are always connected to God. Being still means keeping a still mind, even if your body is moving or you are doing some activity. Then there’s no subject, no object, a mind of complete stillness. That’s the Buddha’s complete stillness mind. When sitting, be still. When chanting, be still. When bowing, eating, talking, walking, reading or driving, only be still. This is keeping a not moving mind, which is only do it mind. We call that try mind.